chapter 38

Builders of Pasts and Futures

In Orhan Pamuk’s tragic novel The Museum of Innocence, the fictional narrator Kemal assembles a massive collection of mundane objects to tell the story of his love for Fusan; the woman he spent decades selfishly pursuing and ultimately destroying. He displays his collection in an abandoned Istanbul apartment that once belonged to his mother– a place where she, too, stored cast-off furniture and old clothes. This apartment was the site of his sexual liaisons with Fusan including one that he claims as the happiest moment of his life.

Pamuk’s book is structured like a guided tour of the exhibit. Kemal reveals his tale with the illustrative help of thousands of Fusan’s snuffed out cigarette butts, scarves, hairclips, ashtrays, a quince grater and other objects he has spent several decades stealing from his beloved. Kemal’s collection creates a path to Fusan, dead at the time of the narration. His museum makes manifest the height of his personal obsession but is also astoundingly similar to the countless historical museums across the globe that preserve and analyze the minute details of a life or event. While these institutions collect for cultural posterity, Kemal does so because these artifacts are the proofs of his life. Through these objects he not only remembers, but also verifies and controls his story. Kemal alone is subject, curator and guide.

Kemal’s things are no longer important in their function as graters or cigarettes. They have ceased to perform their original purpose and now exist as symbols of experience. In this case, experience is not based on past use, but in the object’s role as witness once hidden in the background of important scenes of the narrator’s life or because it was owned, used or touched by someone important to him. Like the details of a mnemonic maze, these objects are the cues that prompt the narrator to reveal his story.

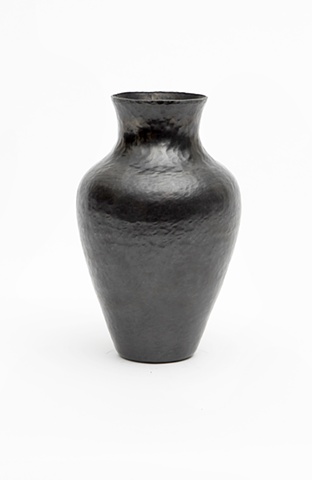

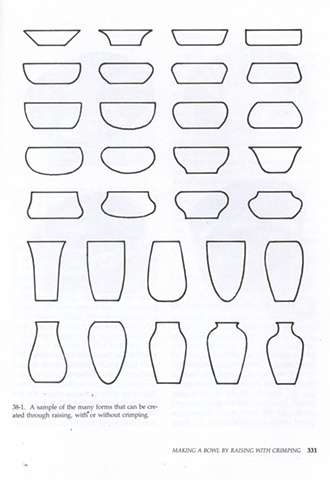

Artist Jeffrey Clancy becomes a similarly obsessed hunter of objects, playing upon the ability of things to transcend function. In Clancy’s work a sample of the many forms that can be created through raising, with or without crimping, the objects are not understood through use. In fact, there is no pretense of use.

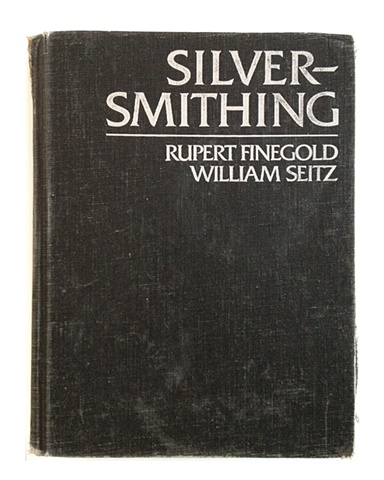

Clancy’s vessel-like objects are based on a technical illustration found in William Steitz and Rupert Finegold’s instructional manual Silversmithing, published in 1983. Although the manual is intended to support the efforts of craftsmen, Clancy did not personally fabricate these forms. This is an ironic fact considering Clancy is among an increasingly limited ilk of craftsmen who possess this unique mastery.

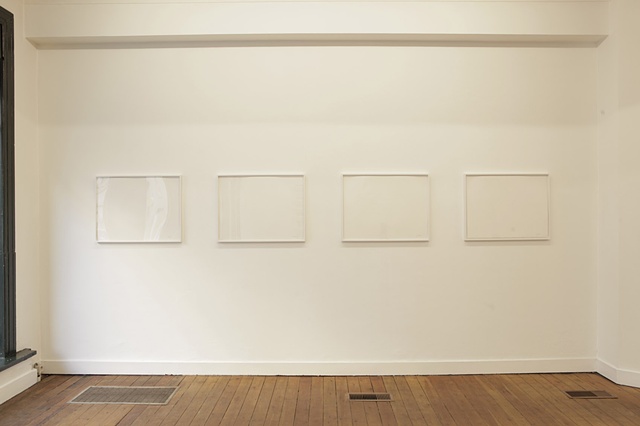

Clancy’s objects are arranged in accordance with Stietz and Finegold’s chart, and placed on shelves that resemble a personal collection. This performance of order convinces us of an intentional logic or history. We are comforted by his display’s sense of care and precision. We trust in its implied mastery.

While Kemal’s objects imprison him within a past he cannot change, Clancy’s objects suggest an array of possible futures. The work is like a menu of potential technical feats. From their ordered shelves, the forms proclaim their own importance, emphasized by the adjacent placement of an oversized copy of Stietz and Finegold’s authoritarian diagram. These works, the result of an anachronistic process now rarely executed, limit their potential to something most silversmiths have left behind. Here, technique, mastery, and process are all literally and metaphorically shelved.

And, perhaps, this is where the soul of the object emerges. These forms represent a specialized knowledge, but offer no rationale for its continued application. This loss is emphasized by the objects’ mournful black hue. Like the objects placed in a museum, their future is limited to their service of the past.

It could be argued that these objects are devoid of all the emotional qualities that enchant us to love our things—ownership, authorship, biography—and yet they are still powerful. Perhaps this is because what we ultimately see is the thing itself– in all its thing-ness. And what do we find? They are black and luminous. They are smooth and cool to the touch. They are symmetrical and solid. They are given order and prominence. Their display implies reason and consideration– even perhaps where there is none to be found. This is proof that objects sometimes have their own stories (and we are merely parenthetical to their narrative).

But what of their keepers? Both Kemal and Clancy rely on the ability of objects to create a narrative. Kemal uses the symbolic and associative qualities of things to happily create a maze out of his own misery. Clancy, on the other hand, does not position his objects as proofs but as questions. While Kemal’s things allow us to come close to his story, with Clancy, the closer we look the more blurred the details become. These objects suggest a man who is no longer reliant on his past, on training, on authority, but willing to gingerly step out into unknown terrain.

-Lauren Fensterstock

Lauren Fensterstock is an artist, curator and writer based in Portland, Maine, where she currently serves as the Academic Program Director of the MFA in Studio Arts at Maine College of Art.